The Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden is sited on land that was once part of the East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve. One of the primary goals of the research taking place through the community garden is to unearth histories that have been silenced by the settler-colonial state, and, through a deeply collaborative research and writing process committed to decolonising methodologies, foreground the voices and stories of Anaiwan, Gumbaynggirr, Dunghutti and Kamilaroi people.

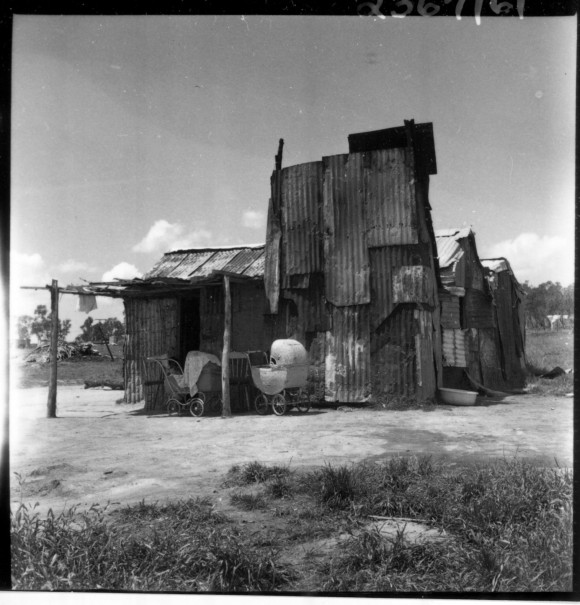

In the 1950s, dispossessed Aboriginal peoples began to gather on top of Armidale’s municipal rubbish dump to glean whatever materials they could to shelter from the below-freezing winters. In her book, Ingelba and the Five Black Matriarchs, Aunty Pat Cohen remembers:

There was about thirty or forty little shacks all around … it was … a rubbish dump where the rubbish was laying around, and the blackfellers, well they made their camp, their huts out of the bits and pieces that were laying around. My mother and her three other children she had … Cliff, Linda and Ollie, were living there. We came back from the Styx River and were living with my mother for a little while until we got a tent and we just pitched a tent behind her … I had a young baby too … There were a terrible lot of deaths out that way. A lot of young kids were dying of diarrhoea … My mother’s husband was Nick White – he died of gastroenteritis – and at one stage I remember there were five young children died within a week from gastroenteritis out there (p.98).

From 1956 until the end of 1961 the East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve had no sewerage and no electric light. In November 1957, when Armidale was in the midst of a severe drought, the Council turned off the only tap that serviced over 80 people living at the fringe camp because they were ‘frightened they would leave it on and waste water’ (Franklin, 57). The tap was still not functioning in February 1958, with an article in the Armidale Express reporting that ‘All shacks… still lack water which has to be carted from a considerable distance as the City Council has not yet restored the supply which was cut off last year’ (Armidale Express, February 10, 1958).

In November 1958, with over 100 people living in tents and shacks on top of the contaminated soils of the town Dump, with one unreliable tap to service everyone, no electricity, and no sewerage, the area was declared an Aboriginal Reserve. Despite now coming under the disciplinary arm of the Aboriginal Welfare Board, the Reserve remained a neglected fringe camp and the much needed and promised basic services – sewerage, water, electricity – were not provided, leaving the segregated Reserve residents to endure a deadly paradox of state neglect and state control.

In early 1960, following two deaths on the Reserve, and the occurrence of serious Gastric illness in four or more children, a Health Officer – Mr Esdaile – was requested to assess the conditions of the site. On the 21st February 1960 Mr Esdaile reported that the Reserve had the ‘most appalling sanitary conditions one could imagine’ with ‘cesspits… full almost to the point of overflowing’ and infestations of maggots and flies throughout the humpies. ‘The only water for all camps comes from a single tap at the extreme southern end of the ground. Many of the inhabitants need to carry all water for domestic needs up to 500 yards’, the Health Report states. In a damning indictment of settler-colonial neglect, Esdaile wrote:

it is quite apparent that the Aborigines Welfare Board is not managing or regulating the use of the Reserve, as they are statuatorially bound to do, vide Aborigines Protection Act, 1909. Absolutely no facilities are provided on the area by the Board, or any body other than the solitary water tap apparently supplied by The City Council…I have no doubt that any infectious disease occurring on the reserve would be transmitted rapidly by the ubiquitous flies and would thrive readily in the conditions prevalent throughout the area. This also constitutes a threat to the health of persons in neighbouring houses an in the City area a few hundred yards away.

Despite the health report recommending urgent action, no changes were made, and seven months later, in September and October 1960, an outbreak of infectious disease spread through the Reserve killing at least four children and hospitalising thirteen in under three weeks. The children ranged from six months to two years of age (Sydney Morning Herald, 13 October, 1960; Sydney Morning Herald, 14 October, 1960).

Following nation-wide outcry at the appalling conditions that had led to the preventable death of children on the East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve, an emergency fund of eighteen thousand pounds was dedicated by the Aboriginal Welfare Board to “clean up” the area, and to build fourteen cottages. Despite the toxicity in the environment caused by living on a rubbish dump that had only stopped being used two years earlier, and the desire of many of the Reserve’s residents to move into town, the ‘Aboriginal Welfare Board maintained that building acceptable houses for Aboriginal people in town would be a waste of money as all the Aborigines needed “training” in “transitional” housing’ (Franklin, 32) because the fringe-dwellers ‘could not yet act properly in a house in town’ (Brereton and Moore, cited in Franklin, 26). On November 7, 1961, referred to by the Aboriginal Welfare Board as ‘Occupation Day’, the tin humpies were demolished and fourteen new cottages were officially opened at the Reserve. These transitional houses had galvanised iron cladding, no heating except for a small stove, no insulation, inadequate bathroom facilities, no hot water, were small and restricted in space, and had no fences. The stark appearance of the corrugated iron earned the Reserve the name of Silver City, and while Elders testify that the new cottages greatly improved living conditions, the substandard dwellings of Silver City functioned as metonym of progress and assimilation in action enabling the Welfare Board to intensify their level of control over the community.

At the time of the building of the cottages, residents were concerned about the surveillance that would now be employed at the Reserve. The District Aboriginal Welfare Officer, Don G. Yates, reassured them that their fears were based on ‘nonsensical propaganda.’ There would be no restriction on visitors, no restrictions to the movement of residents and no invasion of privacy. Don Yates, speaking of himself said, ‘The Welfare Officer will come as a friend ’(Armidale Express, September 11, 1961). Yates’s promises were empty, and the East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve functioned as a paternalistic prison where the dwellings were subject to fortnightly inspections, and the community lived in fear of the power of the Welfare Board to take their children.

Despite the harsh conditions, Elders remember parts of life on the Reserve fondly, as a time of strong families and community connections. The area, now know as Narwan Village, remains home to many families who care for this significant part of town and the memories it holds.

Edward S Casey has written that ‘As much as body or brain, mind or language, place is a keeper of memory – one of the main ways in which the past comes to be secured in the present, held in things before and around us’ (Remembering, p.213). The community garden provides a space for Elders to share their emplaced survivor testimony as a way of fighting the settler colonial state’s ‘violent practices of occupation, erasure and colonial resignification’ (Pugliese, ‘Forensic Ecologies’, p.31)

At the Armidale Aboriginal Community Garden we are enacting an ongoing experimental history project, where survivor testimony and the reclamation of archival materials from colonial institutions, is grounded in place-based memories held in the bodies of the living world that carry memory traces. This more-than-human archive of resistance and remembrance is activated by the speaking of ancestral languages, the practising of culture on country, the creation of hybrid multispecies anticolonial communities, and the public testimony of both human and nonhuman voices that continue to be oppressively silenced in dominant narratives of Australian history.

A paper documenting some of the violent history of the East Armidale Aboriginal Reserve, and the resistance and reclamation by Aboriginal peoples at the community garden, was published in 2019. You can read it here: http://australianhumanitiesreview.org/2019/11/30/place-remembered-unearthing-hidden-histories-in-armidale-aboriginal-community-garden/

References

Cohen, Patsy and Margaret Somerville. Ingelba and the Five Black Matriarchs. Sydney, Wellington & London: Allen & Unwin, 1990.

Franklin, Margaret-Ann. Assimilation in Action: The Armidale Story, Armidale, University of New England Press, 1995.

Pugliese, Joseph. ‘Forensic Ecologies of Occupied Zones and Geographies of Dispossession: Gaza and Occupied East Jerusalem,’ Borderlands, 14.1 (2015): 1–37.

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘4 Children Die: Fear of Gastro Epidemic.’ Thursday 13 October, 1960. p.1

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Poisoning Theory on Ill Aboriginal Children.’ Friday 14 October, 1960, p. 1

Sydney Morning Herald, ‘Appalling Conditions at Armidale Aboriginal Reserve.’ Friday 14 October, 1960.

The Armidale Express, ‘Population Changes at the Dump’, February 10, 1958.

The Armidale Express, ‘Aboriginal Reserve: Conference Clears up Misunderstandings.’ September 11, 1961.